How Sex Education Can Combat Sexual Violence

By Miri Mogilevsky, blogs at Brute Reason

Comprehensive, evidence-based sex education is usually framed as a remedy for the usual culprits: STI transmission, teenage pregnancy, having sex “too early” or with “too many” different partners, and so on. Although this sex-positive feminist bristles at the fact that one of the goals of comprehensive sex ed is to delay sexual initiation and reduce teens’ number of sexual partners, overall these programs are extremely important to promote, and they are effective at reducing STIs and pregnancy in teens—unlike abstinence-only sex ed.

However, I would argue that the goals of secular, scientific sex education should not end there. I believe that we have the responsibility to teach young people sexual ethics and to use education to challenge a culture that too often excuses or even promotes sexual violence.

How do we accomplish such a monumental task? The same way as we teach kids to do school projects: by breaking it down into smaller, more manageable parts.

Rape culture is an ideology that consists of a number of interrelated but distinct beliefs about gender, sexuality, and violence. These beliefs are spread and enforced by just about every source of information that a child interacts with: parents, friends, teachers, books, movies, news stories (on TV, in magazines and newspapers, online), music, advertising, laws, etc..

Traditional, abstinence-only sex education promotes a number of these beliefs in various ways. Here are a few messages that these programs send to teens either implicitly or explicitly, along with how these messages support rape culture:

1. It is a woman’s job to prevent sex from happening.

Abstinence-only sex ed is full of religious ideology, and one example is the idea that women are “clean” and “pure” and must safeguard their own chastity before men can strip them of it. This idea suggests to women that 1) men who keep pushing them for sex are not doing anything wrong, and 2) if they eventually get pressured into having sex, that’s not rape—that’s just the woman not being strong-willed enough.

2. Men always want sex.

A corollary to the previous message, the “men always want sex” meme implies that men who use coercion and/or violence to get sex are only doing what’s natural for them. It also erases male victims of sexual assault, because if men want sex all the time, how could they possibly be raped?

3. Once you’ve had premarital sex, you’re dirty and ruined forever.

Abstinence-only programs promote this idea by using disgusting metaphors like a lollipop that’s been sucked on and discarded, or by having children spit into a glass of water that gets passed around, or by having them rip a paper heart up to symbolize each time they have sex before marriage. Tragically, rapists and abusers use this message against their victims, convincing them that nobody will ever want them now that they’ve been “ruined.” Sometimes this prevents victims from doing anything to try to escape the situation, as Elizabeth Smart attests.

4. Premarital sex is immoral and bad; married and monogamous sex is virtuous and good.

This false dichotomy serves to erase the fact that abuse, sexual assault, and plain ol’ bad sex can happen even within a committed marriage. It may also teach teens to expect that their premarital sexual experiences will all be “Bad” and there’s no avoiding it. This means that teens who are being assaulted or abused may not realize that there’s anything “wrong” with what’s going on; after all, they were warned that premarital sex is bad, weren’t they? Here’s a great take on this from another blogger:

Sex-negative messages don’t keep people from having sex. They keep people from having good sex. They keep people from having pride in their sexuality, from sexual self-awareness. They keep people from asking questions about sex, and communicating with their partners. They discourage experimentation. They blur the lines between consensual sex and rape by framing all sex as an undifferentiated mass of “bad.” They combine victim-blaming with generalized guilt about sex, so that perpetrator and survivor are equally culpable. Basically, they take logic and reason out of the equation.

5. If you have premarital sex, you are a bad person.

Similarly to the last message, the idea that having premarital sex makes you a bad or sinful person erases the distinction between ethical and unethical sex. If everyone who has sex before marriage is a bad person, why bother distinguishing between a bad person who gets consent for sex and a bad person who rapes? Why distinguish between a bad person who rapes and a bad person who “lets” themselves be raped?

There are many more terrible messages that abstinence-only sex education promotes, but I’ll stop there. To be clear, abstinence-only sex ed does not cause these messages to appear in our culture; they were already there. (Religion was probably a major cause, but it certainly wasn’t the whole story.) Children will learn these messages even if they are not religious and do not get this type of sex education.

But abstinence-only sex ed does promote these messages and cause them to become even more entrenched, and failing to challenge them is just about as bad as promoting them, in my view. Educators have a remarkable opportunity to challenge kids’ and teens’ ideas about the world in ways that parents may not be able to. Why not take advantage of that?

A truly evidence-based sex education program must do away not only with lies and exaggerations about STIs, pregnancy, and condom effectiveness, but also with the dominant, rarely-challenged scripts about sexuality that abstinence-only sex ed promotes. Here are some ways to do that. They’re just a start, but they would make a difference.

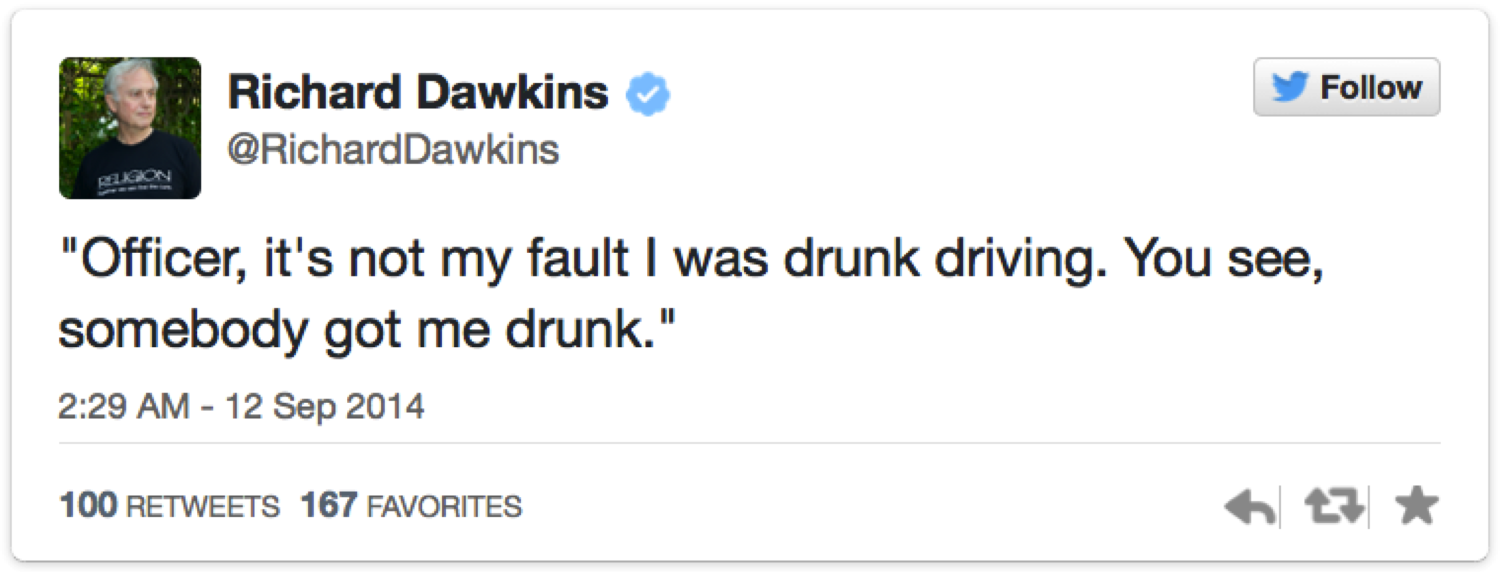

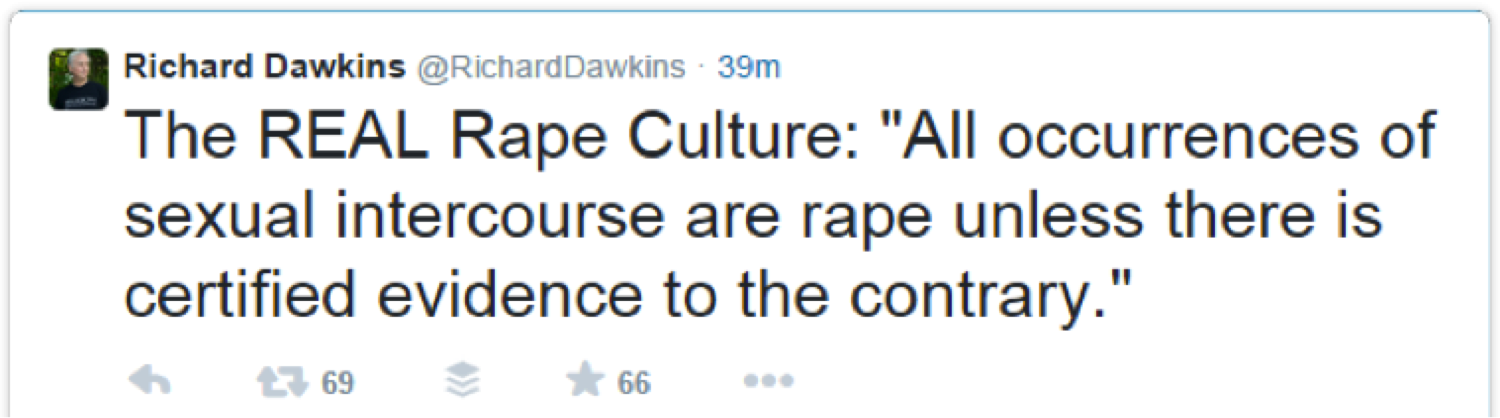

1. Sex education should center consent in the conversation. Consent, rather than arbitrary notions of morality, should be the standard by which we measure sexual activities to determine whether or not they are ethical. Consensual sex, of course, is not necessarily problem-free, but it’s a far better place for teens to start. Conversely, of course, nonconsensual sex (that is, sexual assault) is never okay.

2. It should emphasize that sex and sexuality are not shameful. While comprehensive sex education, unlike abstinence-only, does not explicitly shame anyone for having sex, it still treats reduction of sexual behavior in general (not just of risky sexual behavior) as a positive goal to aim for. That sends the message that less sex is better than more sex, and therefore that there’s something wrong with having sex.

3. It should challenge gender roles and stereotypes. Regressive, inaccurate ideas about gender don’t just keep women out of leadership roles and STEM jobs; they actually cause bad sex in the best case and sexual assault in the worst. The idea that men pursue and women are pursued; that men always want sex and women always want Tru Luv; that women should take it as a “compliment” when they are objectified and harassed—all of these things encourage and excuse sexual assault. Not to mention the fact that they’re extremely heteronormative.

4. It should remind teens that not wanting to have sex is okay. When sex ed programs discuss the option of not being sexually active, it’s usually framed either as a moral choice (in abstinence-only sex education) or as a smart move to prevent negative health outcomes (in comprehensive sex ed). Either way, not having sex is portrayed as a difficult but ultimately superior choice that teens must make by resisting peer pressure and hormones. But in fact, some people are asexual and have no sexual desire or attraction to resist. It’s important to validate this as part of the spectrum of sexual diversity, not only so that asexual teens feel accepted, but so that their peers learn not to pressure them.

5. It should deemphasize (although not completely negate) the importance of relationships and marriage. This is surely a controversial stance and I think nuance is important here. But my reasoning is this: the extreme importance that committed relationships (and especially marriage) are allocated in our society plays a part in keeping people trapped in abusive relationships. Teens who don’t feel that they can experience sex, affection, or love outside of the context of a monogamous relationship may feel pressured to stay in one that they know isn’t healthy, but that is providing them with some combination of those things.

It would probably take a book and dozens of paper citations to fully explain how and why sex education should combat sexual violence. But as these examples show, healthy sexuality is about more than just using contraception and getting tested for STIs. Unfortunately, our culture sends us many negative and harmful messages about sex, but good sex ed can help inoculate kids and teens against them.

About the Author

Miri Mogilevsky is a progressive feminist atheist and a recently transplanted New Yorker. She has a B.A. in psychology and is currently working on a Masters in social work. After that, she hopes to pursue a career that combines activism with counseling. When not doing school things, Miri spends her time reading and writing about social justice, mental health, sexuality, and politics. Occasionally she also interacts with people and sleeps. A few of her other interests include Russian literature, photography, and Cheez-its. In addition, she enjoys asking people about their feelings.

Iris Vander Pluym is an artist, activist and writer based in New York City. Raised to believe Nice Girls™ never discuss religion, sex or politics, it turns out those are pretty much the only topics she ever wants to talk about. A self-described “unapologetic, godless, feminist lefty,” Ms. Vander Pluym blogs at

Iris Vander Pluym is an artist, activist and writer based in New York City. Raised to believe Nice Girls™ never discuss religion, sex or politics, it turns out those are pretty much the only topics she ever wants to talk about. A self-described “unapologetic, godless, feminist lefty,” Ms. Vander Pluym blogs at

Marina Martinez lives in Portland, Oregon with her boyfriend, Ben, her dog, Pepper, and her cat, Medusa. She enjoys being fat, being loud, long walks on the beach, and general awesomeness. You can find her on Twitter

Marina Martinez lives in Portland, Oregon with her boyfriend, Ben, her dog, Pepper, and her cat, Medusa. She enjoys being fat, being loud, long walks on the beach, and general awesomeness. You can find her on Twitter

Sara affectionately refers to herself as a “millennial on a mission.” This mission? Creating a safer world for everyone, particularly women and non-religious folks in all the vast corners of the earth. Sara truly believes that education and cultural awareness will pave the way for tolerance, a virtue desperately needed in these extremely difficult and tumultuous times. Currently earning her Master’s degree in public policy, Sara fights relentlessly for women’s rights and separation of church and state on a policy level by regularly speaking out and lobbying on behalf of these causes. She has written for and worked with several organizations; a monthly columnist for Sacramento Reason and a weekly writer for The Humanist, she hopes to reach an even wider audience through Secular Woman, telling stories, sharing knowledge, and contributing to the growth of the secular women’s movement.

Sara affectionately refers to herself as a “millennial on a mission.” This mission? Creating a safer world for everyone, particularly women and non-religious folks in all the vast corners of the earth. Sara truly believes that education and cultural awareness will pave the way for tolerance, a virtue desperately needed in these extremely difficult and tumultuous times. Currently earning her Master’s degree in public policy, Sara fights relentlessly for women’s rights and separation of church and state on a policy level by regularly speaking out and lobbying on behalf of these causes. She has written for and worked with several organizations; a monthly columnist for Sacramento Reason and a weekly writer for The Humanist, she hopes to reach an even wider audience through Secular Woman, telling stories, sharing knowledge, and contributing to the growth of the secular women’s movement.

Corrina Allen has been an educator in Central New York for the last decade and is the founder and president of the

Corrina Allen has been an educator in Central New York for the last decade and is the founder and president of the